Prevention Program

Recommendations and Considerations

Child Abuse and Neglect Prevention Strategies

- Reduces stigma around help-seeking [1][3]

- Enhances connectedness to build resiliency in the face of adversity [1][3]

- Fosters healthy and positive norms around gender, masculinity, and violence to protect against violence towards intimate partners, children, and peers [1][4][5]

- Promotes safe and effective discipline [1][3]

- Supports ACEs awareness [1][3][4]

- Child development [2][6]

- Expectations for child behavior [1][6][7]

- Behavior management [6][7][8][9][10]

- Anger management skills [2][6][7][9]

- Problem-solving skills [2][6][7][9][10]

- Discipline techniques not involving physical punishment [2][6][7]

- Safe supervision [2][6][7][9]

- Ensuring early childhood home visitation programs meet demand needs [2][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]

- Licensed and accredited child care facilities are available where needed [2]

- Availability of preschool enrichment with family engagement programs that provide parents social support, educational opportunities, and access to community resources. [2][19][20][21][22][23][24]

- Subsidized child care [2][25]

- State and federal earned income tax credit [2][26]

- Section 8 housing [2][27]

- SNAP benefits [2][28][29]

- Livable wages [30]

- Paid leave [31][32][33][34]

- Flexible and consistent schedules [2]

New Programs for Consideration

Upstream USA

Upstream partners with states to provide health centers with patient-centered, evidence-based training and technical assistance that eliminate barriers to offering the full range of contraception.

Cure Violence

Cure Violence stops the spread of violence by using the methods and strategies associated with disease control: detecting and interrupting conflicts, identifying and treating the highest risk individuals, changing social norms. It is a successful evidence-based program with multiple studies showing reductions in violence.

Darkness to Light

Stewards of Children is an evidence-informed, award-winning two-hour training that teaches adults to prevent, recognize, and react responsibly to child sexual abuse. Through interviews with child sexual abuse survivors, experts, and treatment providers, Stewards of Children teaches adults practical actions to reduce instances of child sexual abuse in their organizations, families, and communities.

No Hit Zone

A No Hit Zone is a comprehensive program that includes multiple strategies to effectively influence attitudes, norms, and behaviors. Anyone can become a No Hit Zone! Family homes, schools, hospitals, religious institutions, communities, and many more can join the movement to address the most prevalent risk factor of child abuse-social norms around corporal punishment.

CDC: Essentials for Parenting Toddlers and Preschoolers

Essentials for Parenting Toddlers and Preschoolers is a free, online resource developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Designed for parents of 2 to 4-year-olds,

Jewish Women International

Jewish Women International offers domestic violence prevention training opportunities that empower clergy, social workers, teachers, parents, lawyers, advocates, mental health professionals – everyone positioned to touch a child, teen, adult, or family at risk.

Coaching Boys Into Men

CBIM trains and motivates high school coaches to teach young male athletes healthy relationship skills and that violence never equals strength. A study found that athletes who participated in the program were significantly more likely to intervene when witnessing abusive or disrespectful behaviors among their peers and were also more likely to report less abuse perpetration.

CDC VetoViolence

VetoViolence exists to empower you and your community to prevent violence and implement evidence-based prevention strategies in your community. Tools, trainings, and resources are designed to empower you and your partners to help reduce risks for violence and to increase what protects people and communities from it.

Zero Abuse Project

Programs are designed to provide cross-disciplinary education and training, advocacy for systemic legal change, guidance for survivor support, and leadership on emerging technologies. We take a holistic approach by also recognizing and addressing the intersecting forms of child maltreatment in connection with child sexual abuse.

Existing New Hampshire Community Resources to Explore for Alignment

Alcohol / Opioid Abuse

Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS)

- Hope on Haven Hill

- Dartmouth-Hitchcock

- Memorial Hospital Maine Health

- JSI New Hampshire

- The Partnership

- Families in Transition

- Harbor Care

Asthma or COPD

Lead Exposure in Children

- Lead Safe Manchester

- CDC’s Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program

- DPHS: Healthy Homes and Lead Poisoning Prevention Program

Domestic Violence

- New Hampshire Coalition Against Domestic & Sexual Violence

- Voices Against Violence

- YWCA Crisis Service: Emily's Place in Manchester

- New Horizons for New Hampshire

Assault / Community Violence

Prevention Concepts and Initiatives

In addition to specific recommendations, a population’s concentrated exposure to adverse experiences, including child abuse and neglect, is directly related to negative outcomes; prevention must be a cross-sector, collaborative effort.

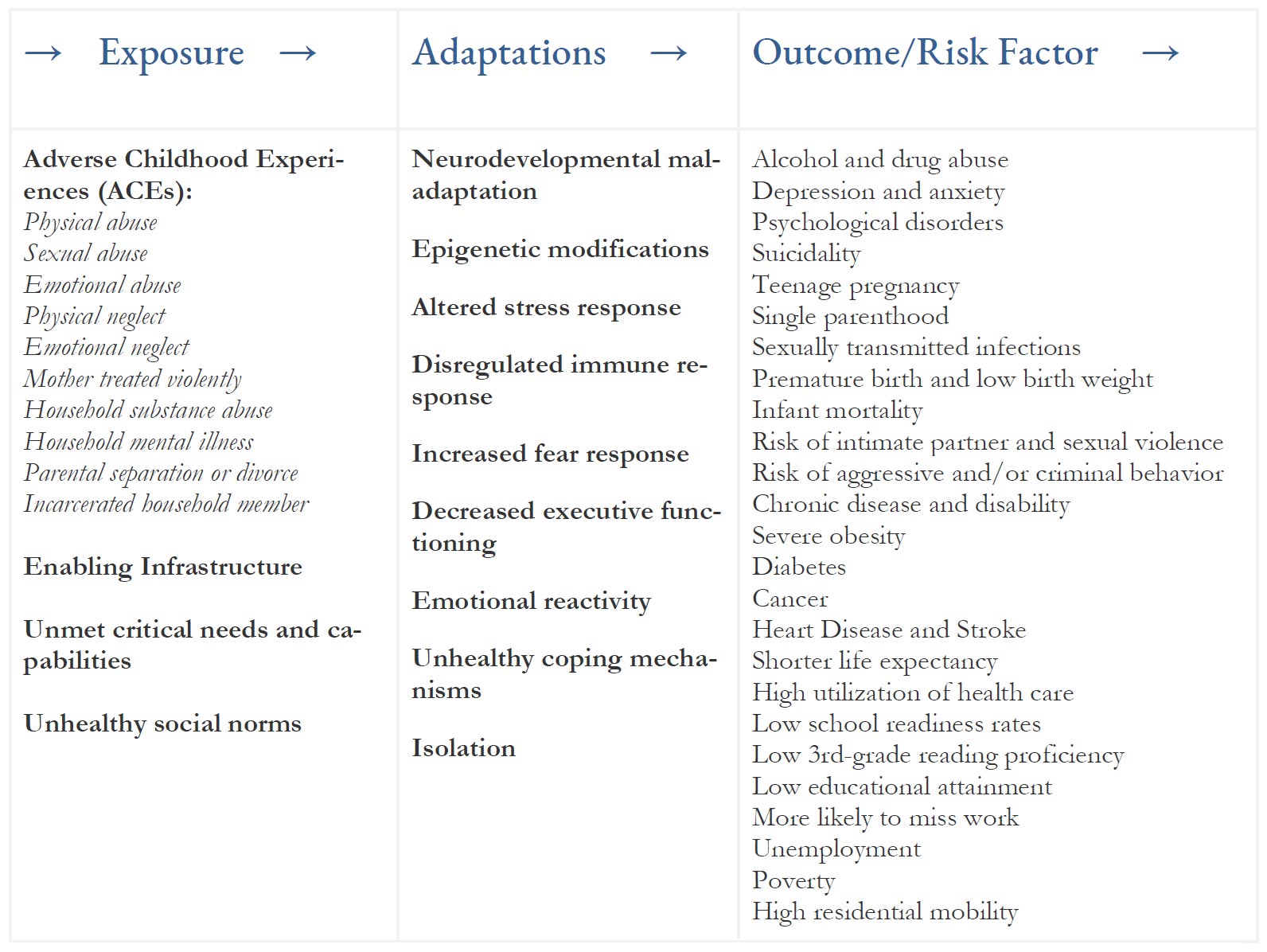

The negative outcomes shown in the chart below are also risk factors for ongoing adverse experiences.

CLICK TO ENLARGE

Hundreds of scientific studies have established these connections, so attempts to address just one negative outcome in isolation are unlikely to be successful.

Therefore, focused efforts to prevent child abuse and neglect must occur in the context of reducing a population’s overall exposure to adverse experiences.

Prevention Possibilities for Further Discussion

Concepts Related to Community-Level Prevention

Child Abuse and Neglect Prevention Initiatives

Specific to High-Needs Areas

Community Engagement and Communication Strategy Development

Recommendations for Optimizing Community Engagement Based on the Manchester Psychographic Analysis Findings

Capitalize on audience insights at most meaningful touchpoints

- High usage in social media: Partner with new mothers’ Facebook groups for events or education to raise awareness amongst the most critical target. Encourage mothers as the group that cares the most about children to stay vigilant and help each other.

- Have little interest in parenting: Partner with clinics to ensure access to long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) is available.

- Careful spenders who only buy essentials / shop at low-end retailers: consider partnering with these retailers as a possible communication channel.

- Low income, economically unstable: Improve financial security by providing well-publicized and easily accessible education and assistance surrounding economic supports such as Section 8 housing, SNAP benefits, WIC, Children’s Medicaid, and CDB child care assistance.

- Smokers who are uninterested in health/exercise, cooking: Partner with CVS/Walgreens/Walmart or other stores that have in-store clinics to introduce healthy options and programs. Create a campaign to increase EBT/SNAP usage at Fresh Food Farms to promote healthy eating.

- Medicaid recipient, medical insurance from a union: Review in high-needs areas which insurances are accepted and if new patients are welcome.

- Unlikely to have dental insurance: Partner with dental clinics to offer discount / low-cost options.

- Eleven to fifteen-year-olds present in household: Educate early partnering with middle and high schools to foster healthy and positive norms around gender, masculinity, and violence to protect against violence towards intimate partners, children, and peers.

- Passionate about music, frequently listening to the radio and free music streaming sites: Prioritize communicating on those channels with educational messaging and promoting social norms conveying community shared responsibility for the well-being of all children. Form partnerships with venues that have live music or sponsor an outdoor concert and share messaging at these events.

Developing a core message: key questions to address

- What are the values and priorities of the audience?

- What is the audience’s current level of awareness about the issue?

- Does our message address the problem, strategy, and call to action?

- While determining the creative development and approach of our messaging, are we keeping in mind real-life stories are preferable to shock tactics and avoiding shaming or finger-pointing?

- Are we choosing media channels such as digital, social, public relations, traditional, etc., based upon analytical research and balancing constraints versus intended results?

Build media advocacy

- Develop relationships with local media: write letters to editors and press releases, focused on the issue and messaging needed for change.

- Share media advisories and media statements that will be introduced by the press, which can create a new or different way of thinking for your audience.

Measuring Communication Effectiveness

As we work towards solidifying our communication strategy, we will create an analytical basis to measure the effectiveness of our efforts.

Communication strategy development will include identifying key performance indicators unique to each approach with measurement solutions that allow for active management so course adjustments can be made effectively to reach our goals.

We will look to develop measurement solutions that:

- Provide objective evidence of progress towards achieving our prevention results

- Offer a comparison that gauges the degree of change of the action or behavior over time

- Measure what is intended to be measured to help inform active decision making

References

- [1] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences: Leveraging the Best Available Evidence. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- [2] Fortson, B. L., Klevens, J., Merrick, M. T., Gilbert, L. K., & Alexander, S. P. (2016). Preventing child abuse and neglect: a technical package for policy, norm, and programmatic activities. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- [3] Stone, D.M., Holland, K.M., Bartholow, B., Crosby, A.E., Davis, S., & Wilkins, N. (2017). Preventing suicide: a technical package of policies, programs, and practices. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- [4] Basile, K.C., DeGue, S., Jones, K., Freire, K., Dills, J., Smith, S.G., & Raiford, J.L. (2016). STOP SV: A technical package to prevent sexual violence. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- [5] David-Ferdon, C., Vivolo-Kantor, A. M., Dahlberg, L. L., Marshall, K. J., Rainford, N. & Hall, J. E. (2016). A comprehensive technical package for the prevention of youth violence and associated risk behaviors. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- [6] Knox, M. S., Burkhart, K., & Hunter, K. E. (2011). ACT Against Violence Parents Raising Safe Kids program: Effects on maltreatment-related parenting behaviors and beliefs. Journal of Family Issues, 32, 55-74.

- [7] Portwood, S. G., Lambert, R. G., Abrams, L. P., & Nelson, E. B. (2011). An evaluation of the Adults and Children Together (ACT) Against Violence Parents Raising Safe Kids program. Journal of Primary Prevention, 32, 147-160.

- [8] Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development. (2015). Incredible Years Parent. Retrieved from https://www.blueprintsprograms.com/factSheet.php?pid=7719a1c782a1ba91c031a682a0a2f8658209adbf.

- [9] The California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare. (2015). SafeCare. Retrieved from https://www.cebc4cw.org/program/safecare/detailed.

- [10] Carta, J. J., Lefever, J. B., Bigelow, K., Borkowski, J., & Warren, S. F. (2013). Randomized trial of a cellular phone-enhanced home visitation parenting intervention. Pediatrics, 132, S167-S173.

- [11] Olds, D. L., Eckenrode, J., Henderson, C. R., Kitzman, H., Powers, J., Cole, R., Sidora, K., Morris, P., Pettitt, L. M., & Luckey, D. (1997). Long-term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect: Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 278(8), 637-643.

- [12] Avellar, S., Paulsell, D., Sama-Miller, E., Del Grosso, P., Akers, L., & Kleinman, R. (2015). Home visiting evidence of effectiveness review: Executive summary. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from https://homvee.acf.hhs.gov/HomVEE_Executive_ Summary_2015.pdf.

- [13] Olds, D. L., Kitzman, H., Hanks, C., Cole, R., Anson, E., Sidora-Arcoleo, K., Luckey, D. W., Henderson, Jr., C. R., Holmberg, J., Tutt, R. A., Stevenson, A. J., & Bondy, J. (2007). Effects of nurse home visiting on maternal and child functioning: Age-9 follow-up of a randomized trial. Pediatrics, 120, e832-e845.

- [14] Mejdoubi, J., van den Heijkant, S. C. C. M., van Leerdam, F. J. M., Heymans, M. W., Crijnen, A., & Hirasing, R. A. (2015). The effect of VoorZorg, the Dutch Nurse-Family Partnership, on child maltreatment and development: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One, 10(4), e0120182.

- [15] Dodge, K. A., Goodman, W. B., Murphy, R. A., O’Donnell, K., Sato, J., & Guptill, S. (2014). Implementation and randomized controlled trial evaluation of universal postnatal nurse home visiting. American Journal of Public Health, 104(S1), S136-S143.

- [16] Nurse Family Partnership. (2011). Evidence-based public policy. Retrieved from https://www.nurse familypartnership.org/public-policy.

- [17] Dodge, K. A., Goodman, W. B., Murphy, R., O’Donnell, K. J., & Sato, J. M. (2013). Toward population impact from home visiting. Zero to Three, 33(3), 17-23.

- [18] Fortson, B. L., Martin, J. B., & Lokey, C. N. (2015). Prevention of child abuse and neglect. In P. T. Clements & A. Burgess (Eds.), Nursing approach to the evaluation of child maltreatment (2nd edition). Saint Louis, MO: STM Learning.

- [19] Reynolds, A. J., Temple, J. A., Robertson, D. L., & Mann, E. A. (2001). Long-term effects of an early childhood intervention on educational achievement and juvenile arrest: A 15-year follow-up of low-income children in public schools. Journal of the American Medical Association, 285(18), 2339-2346.

- [20] Reynolds, A. J., & Robertson, D. L. (2003). School-based early intervention and later child maltreatment in the Chicago Longitudinal Study. Child Development, 74(1), 3-26.

- [21] Reynolds, A. J., Temple, J. A., Ou, S. R., Robertson, D. L., Mersky, J. P., Topitzes, J. W., & Niles, M. D. (2007). Effects of a school-based, early childhood intervention on adult health and well-being: A 19-year follow-up of low-income families. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine,161(8), 730-739.

- [22] Reynolds, A. J., Temple, J. A., White, B. A. B., Ou, S., & Robertson, D. L. (2011). Age-26 cost-benefit analysis of the Child-Parent Early Education Program. Child Development, 82, 379-404.

- [23] Love, J. M., Kisker, E. E., Ross, C., Constantine, J., Boller, K., Brooks-Gunn, J., Chazan-Cohen, R., Tarullo, L. B., Brady-Smith, C., Fuligni, A. S., Schochet, P. Z., Paulsell, D., & Vogel, C. (2005). The effectiveness of Early Head Start for 3-year-old children and their parents: Lessons for policy and programs. Developmental Psychology, 41, 885-901.

- [24] Green, B. L., Ayoub, C., Bartlett, J. D., Von Ende, A., Furrer, C., Chazan-Cohen, R., Vallotton, C., & Klevens, J. (2014). The effect of Early Head Start on child welfare system involvement: A first look at longitudinal child maltreatment outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review, 42, 127-135.

- [25] Forry, N. D. (2009). The impact of child care subsidies on low-income single parents: An examination of child care expenditures and family finances. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 30, 43-54.

- [26] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2015). Policy basics: The Earned Income Tax Credit. Retrieved from https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/policy-basics-the-earned-income-tax-credit.

- [27] United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2016). Community development block grant program (CDBG) and section 8 housing voucher program. Washington, DC. More information is available at www.hud.gov.

- [28] United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). (2013). State options report, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Retrieved from https://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/snap/11-State_Options.pdf

- [29] Gibson-Davis, C., & Foster, E. M. (2006). A cautionary tale: Using propensity scores to estimate the effect of Food Stamps on food insecurity. Social Service Review, 80, 93-126.

- [30] Forget, E. L. (2011). The town with no poverty: The health effects of a Canadian guaranteed annual income field experiment. Canadian Public Policy, 37, 283-305.

- [31] Berger, L. M., Hill, J., & Waldfogel, J. (2005). Maternity leave, early maternal employment and child health and development in the U.S. The Economic Journal, 115, F29-F27.

- [32] Chatterji, P., & Markowitz, S. (2005). Does the length of maternity leave affect maternal health? Southern Economic Journal, 72(1), 16-41

- [33] Klevens, J., Luo, F., Xu, L., & Latzman, N. E. (2016). Paid family leave’s impact on hospital admissions for pediatric abusive head trauma. Injury Prevention. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041702 [e-pub ahead of print]

- [34] Aumann, K., & Galinsky, E. (2009). The state of health in the American workforce: Does having an effective workplace matter? Retrieved from https://familiesandwork.org/downloads/Stateof HealthinAmericanWorkforce.pdf

- [27] Rachel Y. Moon, Trisha Calabrese and Laura Aird (2008). Reducing the Risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome in Child Care and Changing Provider Practices: Lessons Learned From a Demonstration Project. Pediatrics October 2008, 122 (4) 788-798.

- [28] Brandi L. Joyner, Carmen Gill-Bailey and Rachel Y. Moon (2009). Infant Sleep Environments Depicted in Magazines Targeted to Women of Childbearing Age. Pediatrics.

- [29] Rachel Y. Moon, Lauren Kotch and Laura Aird (2006). State Child Care Regulations Regarding Infant Sleep Environment Since the Healthy Child Care America-Back to Sleep Campaign. Pediatrics 118 (1) 73-83.

- [30] CDC. "Folic Acid." CDC.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/folicacid/about.html (accessed July 5, 2020)

- [31] CDC. “Recommendations: Women & Folic Acid.” CDC.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/folicacid/recommendations.html (accessed July 5, 2020)

- [32] [23] Strathearn, L., Mamun, A. A., Najmun, J. M., & O’Callaghan, M. J. (2009). Does breastfeeding protect against substantiated abuse and neglect? A 15-year cohort study. Pediatrics, 123, 483-493.

- [33] Morsy, L., & Rothstein, R. (2015). Parents’ non-standard work schedules make adequate childrearing difficult: Reforming labor market practices can improve children’s cognitive and behavioral outcomes. Economic Policy Institute, Issue Brief #400. Retrieved from https://www.epi.org/files/ pdf/88777.pdf.

- [34] Han, W. (2005). Maternal nonstandard work schedules and child cognitive outcomes. Child Development, 76(1), 137-154.

- [35] Joshi, P., & Bogen, K. (2007). Nonstandard schedules and young children’s behavioral outcomes among working low-income families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 139-156.

- [36] Daro, D., & Dodge, K. A. (2009). Creating community responsibility for child protection: Possibilities and challenges. Future of Children, 19(2), 67-93.

- [37] Richmond-Crum, M., Joyner, C., Fogerty, S., Ellis, M. L., & Saul, J. (2013). Applying a public health approach: The role of state health departments in preventing maltreatment and fatalities of children. Child Welfare, 92(2), 99-117.

- [39] Henley, N., Donovan, R. J., & Morehead, H. (1998). Appealing to positive motivations and emotions in social marketing: Example of a positive parenting campaign. Social Marketing Quarterly, Summer, 49-53.

- [40] Reynolds, A. J., Temple, J. A., White, B. A. B., Ou, S., & Robertson, D. L. (2011). Age-26 cost-benefit analysis of the Child-Parent Early Education Program. Child Development, 82, 379-404.

- [41] Lundahl, B., Risser, H. J., & Lovejoy, M. C. (2006). A meta-analysis of parent training: Moderators and follow-up effects. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 86-104.

- [42] Stannard, S., Hall, S., & Young, J. (1998). Social marketing as a tool to stop child abuse. Social Marketing Quarterly, Summer, 64-68.

- [43] Love, J. M., Kisker, E. E., Ross, C., Constantine, J., Boller, K., Brooks-Gunn, J., Chazan-Cohen, R., Tarullo, L. B., Brady-Smith, C., Fuligni, A. S., Schochet, P. Z., Paulsell, D., & Vogel, C. (2005). The effectiveness of Early Head Start for 3-year-old children and their parents: Lessons for policy and programs. Developmental Psychology, 41, 885-901.

- [44] Taylor, T. K., & Biglan, A. (1998). Behavioral family interventions for improving child-rearing: A review of the literature for clinicians and policy-makers. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 1(1), 41-60.

- [45] Nurse Family Partnership. (2011). Evidence-based public policy. Retrieved from https://www.nurse familypartnership.org/public-policy.

- [46] Dodge, K. A., Goodman, W. B., Murphy, R., O’Donnell, K. J., & Sato, J. M. (2013). Toward population impact from home visiting. Zero to Three, 33(3), 17-23.

- [48] Shonkoff, J., Garner, A., & Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, and Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232-e246.

- [49] Webster-Stratton, C., Reid, M. J., & Hammond, M. (2001). Preventing conduct problems, promoting social competence: A parent and teacher training partnership in Head Start. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30, 283-302.

- [52] Economic Policy Institute. (2015). Irregular work scheduling and its consequences. EPI Briefing Paper #394. Retrieved from https://www.epi.org/files/pdf/82524.pdf.

- [53] Linares, L. O., Montalto, D., Li, M., & Oza, S. V. (2006). A promising

parent intervention in foster care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 32-41.

Cary, C. E., & McMillen, J. C. (2012). The data behind the dissemination: A systematic review of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for use with children and youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 34, 748-757.

Mannarino, A. P., Cohen, J. A., Deblinger, E., Runyon, M. K., & Steer, R. A. (2012). Trauma-Focused Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for sustained impact of treatment 6 and 12 months later. Child Maltreatment,

17(3), 231-241 - [55] [54] CDC. “Preventing Teen Pregnancy” CDC.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/larc/index.html (accessed July 5, 2020)

- [58] [57] [56] The Community Guide. “TFFRS - Violence Prevention: Primary Prevention

Interventions to Reduce Perpetration of Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Violence Among Youth.”

https://www.thecommunityguide.org.

https://www.thecommunityguide.org/content/tffrs-violence-primary-prevention-interventions-reduce-perpetration-intimate-partner-violence-sexual-violence-among-youth

(accessed July 5, 2020).

Brown EC, Low S, Smith BH, Haggerty KP. Outcomes from a school randomized controlled trial of STEPS to RESPECT: a bullying prevention program. School Psychology Review 2011;40:42343.

Coker AL, Bush HM, Fisher BS, Bush HM, Swan SC, et al. Multi-college bystander intervention evaluation for violence prevention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2016;50(3):295302.

Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, et al. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal Preventive Medicine 2002;23(4):2608.

Cox PJ, Ortega S, Cook-Craig PG, Conway P. Strengthening systems for the primary prevention of intimate partner violence and sexual violence: CDC's delta and empower programs. Journal of Family Social Work 2010;13(4):28796.

DeGue S, Valle LA, Holt MK, Massetti GM, Matjasko JL, Tharp AT. A systematic review of primary prevention strategies for sexual violence perpetration. Aggression and Violent Behavior 2014;19:34662.

DeGue S, Simon TR, Basile KC, Yee SL, Lang K, et al.Moving forward by looking back: reflecting on a decade of CDC's work in sexual violence prevention, 20002010. Journal of Women's Health 2012;21(12):12118.

Durlack JA., Weissberg RP, Dymnicki AB, Taylor RD, Schellinger KB. The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development 2011;82(1): 40532.

McMahon PM. The public health approach to the prevention of sexual violence. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment 2000:12(1): 2736.

Smith S, Chen J, Basile K, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010-2012 State Report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017.

Taylor B, Stein N, and Burden F. The effects of gender violence/ harassment prevention programming in middle schools: a randomized experimental evaluation. Violence and Victims 2010;25(2):2023

Whitaker DJ, Murphy CM, Eckhardt CI, Hodges AE, Cowart M. Effectiveness of primary prevention efforts for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse 2013;4(2):17495.

Witte TH, Casper DM, Hackman CL, Mulla MM. Bystander interventions for sexual assault and dating violence on college campuses: are we putting bystanders in harm's way? Journal of American College Health 2017;65:3:14957.

Wolfe DA, Wekerle C, Scott K, et al. Dating violence prevention with at-risk youth: a controlled outcome evaluation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2003;71(2):27991. - [59] For information on data-sharing consistent with FERPA, please refer to guidance provided by ED’s Family PolicyCompliance Office at https://www2.ed.gov/policy/gen/guid/fpco/doc/ferpa-and-communitybased-orgs.pdf

- [60] For more information on implementing positive behavior interventions and supports (PBIS), please visit ED’s PBIS Technical Assistance Center at www.pbis.org.

- [61] Morgan, E., Salomon, N., Plotkin, M., Cohen, R. (2014). The School Discipline Consensus Report: Strategies from the Field to Keep Students Engaged in School and Out of the Juvenile Justice System. New York: Council of State Governments Justice Center. Available at https://csgjusticecenter.org/youth/schooldiscipline-consensus-report/.

- [62] For more information on research findings of Check & Connect implementation, please see https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/interventionreport.aspx?sid=78.

- [63] Ehrlich, S., Gwynne, J. A., Pareja, A. S., and Allensworth, E. M. (2013). Preschool Attendance in Chicago Public Schools: Relationships with Learning Outcomes and Reasons for Absences. Chicago: The University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Reform. Available at https://ccsr.uchicago.edu/publications/preschool-attendance-chicago-public-schools-relationships-learningoutcomes-and-reasons.

Hernandez, D. (2011). Double Jeopardy: How Third-Grade Reading Skills and Poverty Influence High School Graduation. Baltimore: The Annie E. Casey Foundation, p. 6. Available at www.aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/AECF-DoubleJeopardy-2012-Full.pdf.

Utah Education Policy Center at the University of Utah. (2012). Research Brief: Chronic Absenteeism. Available at https://www.utahdataalliance.org/downloads/

ChronicAbsenteeismResearchBrief.pdf.

Nauer, K. et al. (2014). A Better Picture of Poverty: What Chronic Absenteeism and Risk Load Reveal About NYC’s Lowest-Income Elementary Schools. New York: Center for New York City Affairs, The Milano School of International Affairs, Management, and Urban Policy. Available at www.centernyc.org/betterpictureofpoverty/. - [64] Hanover Research. 2016. Best Practices in Improving Student Attendance; Henderson, A.T., and K. Mapp. 2002. A New Wave of Evidence: The Impact of School, Family, and Community Connections on Student Achievement. Austin, TX: Southwest Educational Developmental Laboratory; Sheldon, S. B., and J. L. Epstein. 2004. Getting Students to School: Using Family and Community Involvement to Reduce Chronic Absenteeism.The School Community Journal, 4:2, 3956.

- [65] Moore, K. A., et al. 2014. Making the Grade: Assessing the Evidence for Integrated Student Supports. Child Trends.

- [66] Chang, H. N., and M. Romero. 2008. Present, Engaged, and Accounted For: The Critical Importance of Addressing Chronic Absence in the Early Grades. New York, NY: Columbia University, National Center for Children in Poverty.

- [67] Chang, H. N., et al. 2016. Chronic early absence: What states can do. Phi Delta Kappan, 98:2, 2227; Advocates for Children of New Jersey. 2016. Showing up matters: Newark chronic absenteeism in the early years. Newark: Author.

- [68] Converse, N., and B. Lignugaris/Kraft. 2009. Evaluation of a School-based Mentoring Program for At-Risk Middle School Youth. Remedial and Special Education, 30:1, 3346.

- [69] Herrera, C., et al. 2011. Mentoring in schools: An Impact Study on Big Brothers Big Sisters School-Based Mentoring. Child Development, 82:1, 346361; Klima, T., et al. 2009. What works? Targeted truancy and dropout programs in middle and high school. Olympia: Washington State Institute for Public Policy, 09-06-2201; McPartland, J. M., and S. M. Nettles. 1991. Using Community Adults as Advocates or Mentors for At-Risk Middle School Students: A Two-Year Evaluation of Project RAISE. American Journal of Education, 99:4, 568586; Rogers, L. T. 2014. Absenteeism and Truancy Issues: Are Mentoring Programs Funded by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention the Answer? Children & Schools, 36:3, 185188.

- [70] Railsback, J. 2004. Increasing Student Attendance: Strategies from Research and Practice. Portland, OR: Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory.

- [71] Railsback, J. 2004. Increasing Student Attendance: Strategies from Research and Practice. Portland, OR: Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory; Chicago Public Schools. Safe Passage Program Information.

- [72] Attendance Works and Everyone Graduates Center. 2017. Portraits of Change: Aligning School and Community Resources to Reduce Chronic Absence; Chang, H., and P. W. Jordan. 2012. Building a Culture of Attendance: Schools and Afterschool Programs Together Can and Should Make a Difference! The Expanded Learning & Afterschool Project.

- [73] Hanover Research. 2016. Best Practices in Improving Student Attendance.

- [74] Epstein, J. L., and S. B. Sheldon. 2002. Present and Accounted for: Improving Student Attendance Through Family and Community Involvement.Journal of Educational Research, 95:5, 308318; Ford, J., and R. D. Sutphen. 1996. Early Intervention to Improve Attendance in Elementary School for At-Risk Children: A Pilot Program. Social Work in Education, 18:2, 95102; Railsback, J. 2004. Increasing Student Attendance: Strategies from Research and Practice. Portland, OR: Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory; Reid, W., and C. Bailey-Dempsey. 1995. “The effects of monetary incentives on school performance.” Families in Society, 76:6, 33140.

- [86] Julia Lara, Ph.D.; Kenneth Noble, Ph.D. Stacey Pelika, Ph.D., Andy Coons. (2018). https://www.nea.org/assets/docs/Chronic%20Absenteeism%20NBI%2057-2017.pdf (accessed July 5, 2020).

- Daley D., Bachmann M., Bachmann B.A., Pedigo C., Bui. M.T., & Coffman J. (2016). Risk terrain modeling predicts child maltreatment. Child Abuse Neglect. 62:29-38. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.09.014. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0145213416301922

- Predict Align Prevent (2019). Richmond, Virginia Technical Report. https://b9157c41-5fbe-4e28-8784-ea36ffdbce2f.filesusr.com/ugd/fbb580_2f1dda2ff6b84f32856bc95d802d6629.pdf